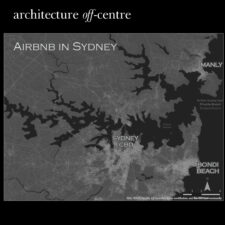

We are no strangers to the AirBnB phenomenon – and how it has revolutionized the travel industry. Over the last two episodes, we have been focusing on the rental housing markets in Kenya and India, and today we’ll take pan over to Australia to see what the short-term rental market looks like.

Dr. Thomas Sigler is an academic researcher in urban and economic geography. He holds a PhD and MSc from the Pennsylvania State University, and a BA from the University of Southern California. He is an Associate Professor and Deputy Head of School in the School of the Environment at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, and a Guest Professor of Geography at the University of Luxembourg.

About Dr. Sigler: https://environment.uq.edu.au/profile/9602/thomas-sigler

Transcript

Vaissnavi Shukl

We are no strangers to the Airbnb phenomenon and how it has revolutionized the travel industry. Over the last two episodes, we have been focusing on the rental housing markets in Kenya and India, and today, we’ll pan over to Australia to see what the short term rental market looks like with the support of the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, we speak to economic and urban geographer Dr.Thomas Sigler on how the sharing economy and short term rentals have evolved in Australia and what impact they have on the larger housing market.

I am Vaissnavi Shukl, and this is Architecture Off-Centre. A podcast where we highlight contemporary discourses that shape the built environment but do not occupy the center stage in our daily lives. We speak to radical designers, thinkers and change makers who are deeply engaged in redefining the way we live and interact with the world around us.

Since we’re talking about things short term rentals today, I thought we’ll start with just talking about the evolution of the sharing economy and little bit of a brief history of short term rentals in Australia, and when we spoke for the first time, you mentioned a little bit about how technology played a role in developing the whole access to short term rentals, both from the user side and the provider side. So short term rentals technology and the sharing economy.

Thomas Sigler

Yeah, so the share economy was an outgrowth of a number of different processes. One which you mentioned was this digital revolution. It transformed a bunch of systems that were already in place as what we might think of as P to P, or peer to peer systems, into digital systems. And this was true across the board. So there are peer to peer systems for sharing or for dividing resources in terms of clothing, transportation, accommodation, assets and goods. There’s lots of different things that became amplified with the digital transformations that occurred about 20 years ago. The biggest sort of catalyst for all of this was the development of the smartphone. So the smartphone essentially just accelerated what was already in place with simple mobile telephones, and it allowed for things to be applied. Very existing systems emerged. Lots of different sharing economy providers, both small and large, emerged from about 2007-2008 onwards. So really exponential growth in the share economy in the early 2010s. And that’s taken a little bit more recently as what we might refer to. Providers like Airbnb, Uber have taken over significant market share in a much more commodified way, so that the event, the advent of Airbnb and other short term rental platforms and modes, I should say, not just platforms, was really an outgrowth of the sharing economy. And the sharing economy was really exciting, I think, in the first few days, it was really characterized by a lot of innovation and new ideas, and it was also badged as something that could promote sustainability, in that if you had an asset that was lying dormant, for example, a vacation house, you could allow other people to use it for certain parts of the year, and then it would be better utilized. Your idea for Uber was very similar to how people could give rides with excess capacity in their vehicles. For example, if you commute from A to B every morning and someone else in your community needs to go, you can share that. But again, over time, I’d say, especially from about 2013-14, onward, as larger pools of capital started investing in the sharing economy, many of these platforms got quite large, and they started running much leaner, much more commercialized models.

Vaissnavi Shukl

Let’s focus a little bit on Airbnb as a typical placeholder for short term rentals on the platforms that kind of aid that kind of property sharing or property lending. So how do you think Airbnb has transformed the concept of shared economy beyond just housing? So I’ll focus a little bit on housing, because the Airbnb model is significantly different from other short term rentals that exist in the market usually. So if you were to go live in a city and rent an apartment for a summer, it would be different than getting an Airbnb. How do you think this this technology and this brand of short term rental, whether it’s vacation, whether it’s for business leisure, maybe has has changed how housing rental works otherwise, and from there, I was also want to talk about how this has led to a certain professionalization of this short term rental, and how do you see it developing in Australia? How has it happened? How do you see it happening?

Thomas Sigler

Yeah, so Airbnb has related platforms. When I say Airbnb, I’m sort of using shorthand for providers. Airbnb really transformed housing markets in particular, in several ways. The first of all is just the amplification, the digitization of the process, you’ll find, increasingly, there’s pressure on the real estate industry, property managers, landlords. There’s a whole suite of actors involved in the conventional rental market, and I wouldn’t say that they don’t need to exist, but I would say particular tasks can be automated and replaced by digital platforms and technology, and that was very slow to change. A lot of these processes, like property management, are big sectors. They’re very lucrative. But Airbnb changed all of that. So all of a sudden, people realize the potential of a digital platform where everything from a bond or escrow payments could be held to issues could be resolved. They could be centrally managed. A lot of information can be disseminated very quickly in both directions. And the app could take more of a third party role and a transactional role. And you know, the host or the property manager and the owner would interact with the tenant to the guest in, I guess, new and simpler ways. It also opened up some possibilities for the short term and I observed over the years that this is really just filling an existing market gap. What I usually say is that we’re really good at long term rentals, so there’s a lot of rules and a lot of possibilities for leases of six to 12 months and longer. And in many contexts, it’s not uncommon to have a lease of five years in Australia in particular, most people get six degrees, and we’re really good at deploying hotel rows. There’s a whole system established and lots of rules and lots of regulations and possibilities for people wanting to stay at a property for one to three nights, which is typically a hotel. Anything that falls in the middle of that was a bit of a gray area, and that’s where Airbnb picked up the slack. So it’s not that they were necessarily trying to wrestle properly for long term rentals or hotels. It’s that there is genuinely a cohort of people that need accommodation for between two and 180 nights that really have nowhere to turn. Oftentimes, these people were visiting for really diverse reasons. So they could have been temporarily working. They could have been visiting family, or they could just be holidaying, but they also have different requirements. So for example, families require extra bedrooms. Often want to cut costs in restaurants by cooking. People want to do laundry about an extended trip. So the characteristics of a short term rental are actually, in many cases, quite different, and we’ve seen that in the data in different contexts, there’s also a lot of variation by GDP. There’s variation by type, in terms of some markets being primarily hosted markets and other markets being primarily unnoticed markets.

Vaissnavi Shukl

If you were to do a little bit of a thought exercise in just seeing what the future would look like, if the existing market that accommodates for the six to 12 month lease, they ever interested in getting into short term rentals. So you have condominium developers, you have apartment buildings landlords who usually do long term leases. You know, you go through the process of documentation, you have your security deposits held, and then just to think out loud if they were interested in getting into the short term rental market in that smart Airbnb. Do you think that’s a possibility, or do you think we’ve now reached that stage in shelter, speaking broadly, where platforms like Airbnb have monopolized it so much that now in traditional leasing and renting short term becomes a little bit of a hassle. Would you say that? Or do you think there’s still a possibility that we can find alternate modes of leasing which are not dependent on platforms like booking.com.

Thomas Sigler

Yeah, I mean, you’re already seeing this to a great extent, with modes like build to rent. So the build to rent sector is essentially a short term rental accommodation sector for long term renters. The US has a significant build to register, which it refers to as multifamily. In the UK, in Australia, for example, build to rent is very immature, but it looks a lot like short term rentals, at least they’re not necessarily an increment of six or 12 months. And the whole platformized system of collecting and signing leases is already percolating through. There’s lots of sorts of digital landlords, digital leases, all kinds of digital technologies that are just making the process easier. Now, the issue, of course, is consumer protection. So the idea that housing is a public good and that it’s the government’s responsibility to ensure some level of safety, security and continuity in that does contradict this idea to some degree, the idea being that there’s a reason leases are conventionally six to 12 months, which is that the government would like the tenant to have a certain amount of certainty that they won’t be displaced or evicted if the landlord wants to sell or pursue a higher rent payment from another tenant or just doesn’t like the tenant for whatever reason. So I think there’s a balance to be struck. It’ll look different in every jurisdiction because the delegation of responsibilities between the private sector and government looks different in every jurisdiction. But I think there’s a place for digitization and amplification in the long term rental market, but I don’t necessarily think that’ll come from Airbnb. The data indicate that Airbnb is sort of not losing absolute market share, but I would say they’re losing relative market share as new players and new entrants start discovering that there’s a fairly robust combination sector out there. You’re seeing third party apps like Airbnb and booking.com which are purely intermediary platforms entering the market, but you’re also seeing really large hotel providers, and increasingly private equity companies and actors are getting involved because they see dollar signs in both those cases.

Vaissnavi Shukl

Thomas, whether it’s, it’s the intermediaries like booking.com or the hotel providers or, I mean, landlords typically wouldn’t be on the same roster. What does it do? The short term rental model itself, the proper practice. What does it do to real estate? Do you think it really depends on whether it’s a luxury vacation rental versus a more business-like rental in the middle of a city or do you think short term rentals have actually influenced the way property rates are seen fluctuating in cities around.

Thomas Sigler

Yeah, it’s an interesting question. It’s one I get quite often. We’ve done some research on this, and in sort of geographical terms, we refer to this as the red gap. And the red gap essentially refers to what you could be receiving on in some other mode and what you are receiving so we’ve done some research, for example, here in Queensland, Australia, where we found that the rent gap between long term and short term rentals exist, but it’s very place specific, and it tends to be place specific around areas with high amenity. And the reason is, most tourists don’t have a car, so most tourists are visiting and they’re staying somewhere that’s walkable. They’re staying somewhere that’s near public transportation. So in locally specific areas, for example, near the or near a central business district or near a transit hub, there tends to be much higher prices on short term rentals than long term the exact opposite is true in the outer suburbs, because tourists or visitors often don’t have a vehicle. They’re often unfamiliar with the region. They’re often not willing to pay a premium. And the thing to keep in mind is that this is a dynamic market. Both and short term rental prices are continuously fluctuating, and oftentimes one overtakes the other depending on market conditions. And so actually, what you’ve seen in the last six months is a softening of short term conditions and a hardening of long term conditions. And in some of our research, we’ve observed quite a few properties that have come off the short term market onto the long term question. Directly, I’ve seen research indicating that short term markets push the price of housing up between about one and 3% and that’s it that’s in a conventional market. It’s a little bit exaggerated in southern Europe, because the difference in Northern Europe is quite distinct to what you charge in southern Europe for local markets. So examples being Venice, Lisbon, Florence, a lot of those markets tend to have quite exaggerated prices between what they’re able to charge tourists and what they’re able to charge locals. But in an environment where most of your visitors are actually domestic visitors like Australia, and most of your tenants are tenants. Or by definition, I guess all, there is a terribly large met gap.

Vaissnavi Shukl

What can be said about the occupancy between the different modes?

Thomas Sigler

Yeah, it really varies, so that the main determinant of occupancy is type or location. So, we find.

But then you find other times of year, for example, October and May, occupancy might be at 20 or 30% for the average property. So it’s highly varied. You’ll find occupancies tend to be higher in major cities because there’s a more steady flow of visitors year round. Of course, that does vary. Certain cities are much busier in the summer. Other cities are in warm warm areas. For example, Darwin is actually much more popular in the winter because it’s relatively cooler, whereas it’s blazing hot in the summer. So overall, you’re seeing occupied seas intensifying. I think hosts, because of rising interest rates, are a little bit more money conscious than they were 5-10 years ago, and trying to squeeze more out and get more professionalization. hosts and professional property managers perhaps have greater attention to the market, a little bit more of a pulse in terms of what they can charge and the occupancy rates tend to be higher in professional managed properties, you know.

Vaissnavi Shukl

While talking about all of this like the business aspect of it and seeing how people are paying to get an accommodation, whether it’s a hotel, it’s an Airbnb. I was 21 living in Europe as an exchange student, and I was, you know, I went backpacking, and I don’t know if it still exists, there used to be a platform called couch surfing, which had a little bit of a soda towards it’s not rental. It’s literally like finding a place and crashing at somebody’s place. But that the social angle made it so interesting, where you could go to a different city, stay with a local person, pretty much like Airbnb, maybe, but you just don’t pay for it, like you just go and you crash on somebody’s couch. I don’t know if the social angle is something that comes into play. I mean, some AirBnB, of course, will have a host who will, you know, go after the way and do that. I thought was a very interesting model, because you didn’t have to pay for it. There was just a platform where people could put their couches, number of people they could host. You could find, you could write to them. And it was actually a lot of fun, because, you know, they would be showing you around to places that you would typically have not explored as a as a young student. And you know, we were in Berlin, we crashed with a couple who were artists, and they took us to this festival. And those are the kind of things I don’t know if they would ever become a part of an experience. Now, of course, Airbnb and booking.com you can actually book experiences with different hosts, and you have super hosts to do this and that. But I just thought that was a very interesting model where just the financial side was completely taken out of it, and you were just banking on the social aspect of it.

Thomas Sigler

So Airbnb is a direct outgrowth of couchsurfing. The original concept was three guys and a mattress in San Francisco. And it was during the I think, Democratic National Convention, there were a lot of people in town looking for rooms, and so they rented out there essentially a spare mattress on the floor. And that was the beginning of Airbnb, which was pretty much the couch surfing model, except monetized. To be fair, you do have lots of sharing economy platforms that are non monetized. You’ve got lots, especially things like food sharing, clothing. I think they really speak to Gen Y. What do you mean when you say food chain? Sorry, if a restaurant over produces food for an event, they might be able to put that up. Hey, we have 100 additional bread rolls if you’re in if you’re running event, let’s say a children’s soccer event, and you’re looking for some surplus food, you can come and get it for us for free. So just allowing people to access surplus or garden vegetables, for example, if you have a garden that has vegetables you can’t consume, you could offer the community to come over and harvest those for you, and then they would get to take some home. So lots of sort of goodwill initiatives. Clothing is a big one. So both monetized, really speaking to the sustainability preferences of Gen Y and Gen Z. We’re so used to fast fashion with, for example, Zara and H&M. You might buy a shirt and wear it twice, and then it’s a perfectly good shirt, but you’ve already gotten to Instagram photos in it, and then you might, you know, you might just say, “Hey, anyone who wants this can have it for the price of postage”, knowing that, you know, there’s so many different aspects to any kind of sharing.

Vaissnavi Shukl

If you could add a little bit of light on what Covid did to the short term rental market. Obviously, people were not traveling. Travel was at a full stop. People suffered a lot of losses. What was it like in Australia during the pandemic, and what was the recovery?

Thomas Sigler

Yeah, I can really only speak to Australia on this one, but our borders were totally shut for almost two years, which means that there was zero international visitation. This had a particularly challenging impact on Sydney. Sydney’s the sort of gateway for international visitation, and in certain areas that revealed international visitors, like the winds, Sunday islands or Cairns or Melbourne, to a lesser extent. So what happened is a lot of those properties either sat vacant, they were sold because there were rising property prices, or they were converted back to long term rentals. In two years since the pandemic has sort of finished, some of those properties have made their way back onto the short term rental market, but in a much more professionalized form. So I think what we’ve observed in other sectors we’ve studied is that it has an accelerating effect. Didn’t necessarily have a transformational effect, but it had an accelerating effect to advance processes that were already in train, specifically the professionalization of property. So we find that we can see this in the data. If you look at the number of posts with more than two properties, we consider the professional. We consider them an amateur professional if they have two to three properties, and then a professional professional, if they have more than five properties, doesn’t mean they own them, but it means they manage them. So these properties are managed like hotel rooms. They’re they’re provided with the same amenities, clean towels and soap and things like that. And the uses have intensified. And you know, the markets have really, really been shaped here in Australia by the domestic, domestic market. The last few years, it’s been a push to the region. So that’s outside of major cities. There’s been a huge amount of Airbnb demand in my state, of which, relatively speaking, we were open for business during the pandemic in that our state border was closed, but domestically, we were really free to travel. And the other reason is Queensland as a resource based state, and you the resources economy has continued to perform well, and you have a lot of short term travel relating to that. So people who are working in the mines and working in oil and gas, and you can see that very clearly in the data, the regions that are what you might call non conventional accommodation markets have done really well.

Vaissnavi Shukl

You alluded a little bit to the city and the areas outside of the city. What the urban rural divide, if there is any, looks like, and I know you studied this phenomena of the urban, rural short term rental markets across the world, especially between India and Australia. Have you noticed some changes in terms of how access to technology actually changes, the way properties are offered or properties are sought after. From a global perspective, what’s your overall decision on this difference?

Thomas Sigler

Yeah, there’s, there’s a lot of distinction between urban and rural properties. Part of it is policy. So housing is a lot more competitive in cities, and therefore urban policy is a lot more, I would say, anti short term rental than regional and rural policy. A lot of regional and rural areas in Australia are quite keen to host tourists and recognize that short term rental is often the only form of accommodation, if not one of the only forms of accommodation, for example, in parts of Tasmania or parts of states that are far away from our major capital cities. You also tend to get many more properties in cities. And therefore, I think it’s seen as more of a policy issue than perhaps in regional areas. But the main, I guess, the main policy spearheads in Australia tend to be areas that are overwhelmingly characterized by the tourism economy. So Byron Bay is a really good one to look at, Douglas and Nusa, where in each case, something like 10 to 20% of the housing stock is short term models. And I don’t think that’s a problem as such, the issue is that often essential workers have challenging conditions, finding accommodation, and I think finding the right balance there is often and again, I’m talking about this in the context of rural versus urban, because in cities, we have lots of housing. So in theory, there is a solution that could be achieved through subsidies or some other form, but in regional areas, just not a lot of housing to begin with, and so oftentimes, small supply can lead to exaggerated outcomes and demand.

Vaissnavi Shukl

something that we’ve been seeing in India even right now with a lot of organizations, Whether they are nonprofit organizations or cooperatives or farmer collectives, kind of coming together to enable farm owners or people who run small scale businesses and offer up their houses as experiences. So there’s a couple of platforms, which are farm-stays in the south and west of India. There are a couple of platforms which have, well, you wouldn’t say it’s a short term rental, but the duration ranges from 15 days to three months. And those are located just in the hills, in areas which have no so there’s a lot of these very niche platforms plotting up where they’re identifying properties, property owners, people who are able to, you know, offer experiences and kind of bring them together. The interesting thing, however, is don’t know if this has to do with just the way they are putting them out, but these properties don’t exist on Airbnb for some reason. So they don’t exist on booking.com, they don’t exist on Airbnb. They’re just there as independent platforms, where only if you knew about this particular farm stay cooperative, three hour radius from Mumbai, you would know about it. And then you go there and similarly with the mountain ones. Do you think there are any such alternate platform initiatives popping up in Australia? Or do you think because of the access to technology, a lot of people have been able to formalize it and just put it upon Airbnb platforms like that, and just centralize it, rather than off shooting into more independent collectives?

Thomas Sigler

Yeah. Look, I think it’s important to stress that Australia has always been a tourism economy. There’s always been a lot of tourists, and there’s always been a lot of appetite for experiences and accommodations. So none of this is new. A lot of it’s been put on digital applications, and a lot of it’s been AirBnB-ified. But this is not the first time the tourism economy has shifted, and it’s not the last time it will shift. So you know, I guess from the perspective of regional and rural tourism operators, if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it if existing word of mouth is enough to supply their business with customers. But I think that’s totally fine. I do think it’s a matter of preference, though, there were strong pushes against Uber about 10 years ago, and what they realize is young people, especially really like the idea of ordering a taxi on both so regardless of the fact that it’s cheaper than a conventional taxi, it’s that idea that you can order something on your phone and that you can be you don’t have to talk to a human being. And I think that’s just a Gen Y and Gen Z press in general. So to answer your question, I do think ultimately a lot of things will be amplified, slowly but surely.

Vaissnavi Shukl

Well, the tourism industry, how there have been shifts, how do you see it shifting from now on. Do you think there are other modes which will probe up that we aren’t fully teaming or you think there are different modes that will take a new avatar and just keep on reinventing themselves, depending on how tourism and global movements tend to affect the overall human population across the world?

Thomas Sigler

Yeah, look, I mean, it’s a work in progress. Think the one thing that’s really matured in the last two, three years is the regulation. I think covid was really a time for a lot of places to pause and think hard about their regulation, because tourism came back with a vengeance after covid, and so I think the maturation of regulation has really shaped Airbnbs and short term rental markets around the world the last couple of years. If that happens, I would say that we’re going to continue to corporatize the model. My guess is that players, and this is already happening, Hilton Marriott, Sheraton Novotel, all the big hotel players in the world will see a lot of opportunity in short term rentals. And my suspicion is that there actually won’t be too big difference between a conventional lease, a short term rental and a hotel stay in 50 years, waiting for the time to come,

Vaissnavi Shukl

But until then, Thomas, thank you so much for your time, and we hope to read more of your research and see what you’re doing next.

Special thanks to Ayushi Thakur for the research and design support, and Kahaan Shah for the background score. For guests and topic suggestions, you can get in touch with us through instagram or our website through our website archoffcentre.com, both of which are ‘archoffcentre’. And thank you for listening.