“Pyaavs today really could be instigators and facilitators mainly as drinking water fountains [but] at the same time also create a cultural connect and socio-cultural tourism.”

Not too long before potable water became a commodity that could be bought and sold, its presence in the Indian urban infrastructure as drinking water fountains – or pyaavs as they are known in Mumbai – was closely associated with altruism and public memory. Our guest, Rahul Chemburkar, is on a mission to restore the pyaavs and activate the space around them to become thriving socio-cultural hubs of urban life.

Architect and heritage enthusiast Rahul Chemburkar is involved in conserving varied built heritage through his firm Vaastu Vidhaan by successfully reviving & rendering a glimpse of a glorious past to the current society.

To follow Rahul’s work on the pyaavs: https://www.vaastuvidhaan.in/The-Pyaav-Project.html and https://www.instagram.com/p/CQufeJpJ_9u

Transcript

Vaissnavi Shukl

Not too long before portable water became a commodity that could be bought and sold. Its presence in the Indian urban infrastructure was closely associated with altruism and public memory. The drinking water fountains, or pyaavs, as they are known in Mumbai, were commissioned by respected community leaders to provide clean drinking water free of charge and were often constructed in memory of a beloved family member. With the advent of packaged drinking water and implementation of modern time planning policies, the centuries old network of payoffs met with neglect, our guest today, Rahul Chemburkar, is on a mission. to restore the pyaavs and activate the space around them to become thriving socio-cultural hubs of urban life.

My name is Vaissnavi Shukl and this is Architecture Off- Centre, a podcast where we highlight unconventional design practices and research projects that reflect the emerging discourses within the design discipline and beyond. Architecture of Center features conversations with exceptionally creative individuals who have extrapolated the traditional fields of Art, Architecture, Planning, landscape, and urban design.

Vaissnavi Shukl

Okay, we’re all set. And I’m very excited to have you on the podcast today. So, thank you for being here. To start off, can you tell us what the pyaavs are? And can we talk about how you came across these paths in a city particularly known for its colonial architecture and art deco buildings.

Rahul Chemburkar

So, the pyaavs are simple drinking water fountains. To start with, that’s a very simple idea and that drinking water is a very basic necessity of all human beings, all living beings for that matter, and when it comes to a busy city like Mumbai, try right from its initial stages, as we know the city has been it has a very urban kind of nature and every it is on the move in context to every every century. So, obviously, the need for drinking water has been there. And therefore, we in the colonial times, during the British era, when Bombay was a very busy city, then you can see these interesting drinking water facilities, which are in the form of very aesthetically created fountains, drinking water fountains, which colloquially are mentioned as houses. So that’s just to start with to introduce you to the chaos. The word pyaav, also, if you see phonetically, and it has that we can’t say exactly how it must have originated. But it seems it’s a confluence of maybe the colloquial or the local language to mean ‘pyaas’ this these others just hypothesis, and then it’s not that it could also have maybe I was discussing with one of my friends, who’s a social historian, it may have a connection related to maybe Aqua, you never know. Because the institution or these fountains are inspired or you know, the idea may have been taken from the European drinking water fountain, which you see dotting those streets of countries like Italy or UK, if you for that matter, even I think, very contemporary drinking water fountains in the states also. So of course, you may have encountered a few. So of course I will because now people know that I’m working on the fountains, many of my overseas friends, when they come across, they definitely you know, they make it a point that “Okay, we saw the fountain today.” So I think when it comes, you know, the intrinsic value, I would say of the house is that it’s a confluence of the European drinking water fountain and the interesting socio cultural elements of which are inherent to the Indian culture, namely charity and association value or memory, because the pyaavs are funded by many philanthropist in those times in memory of someone very near who has passed away. So you see this is dedicated to those near and dear ones, but the interesting thing is that it is for the whole city. It is not only so even if it is from a community, let’s say if it is come from a community or a coolie community, it’s not that these is these are meant for only that community, it is for the whole city and that makes it very interesting and therefore, I every time say that without making it very loud, without having this kind of a declaration that cook a two year is a plough which is built etc etc. It is just somebody standing there and doing its duty giving you shelter or just a resting place and just having a mouth full of water to quench the thirst. But it is esthetical data. It is not just. It is not like the water ATM. I call it a Water ATM of which you see today in the railway stations of India where you put some coins and out comes the bottle but it doesn’t have an appealing feel. It’s like you know it is not inviting, it is actually becoming a commodity, commercial commodity. But in contrast to this the powers of the yesteryears are inviting they haven’t free, they invite you and they create a cultural correct,

Vaissnavi Shukl

Right. It’s interesting you bring up the question of the existence of the Water ATM. Water is a scarce resource in India, at least potable water is. And we are now seeing ATMs and such being provided in a lot of public spaces which are paid public sources of drinking water. But the pianos were originally built with the intention of providing free drinking water. Now with the increased population and the shortage of water supply, what do you think the role of the house is, especially in terms of water charity, like not looking at the intention that they were originally built with? But in a contemporary scenario where all these other sources exist, where do you pay for a basic humanity? What do powers mean right now, and if I can probe a little more, what kind of role can the government and public policy play in sustaining the use of powers as a free water drinking resource because, you know, when we talk about it, especially in the Indian scenario, the three main pillars of roti, kapra and makaan, and broadly speaking, air as something that you don’t pay to, to breathe and water which, until of course, capitalism started packaging, it was also supposed to be a free resources, especially with that mindset. How do we look at pals today?

Rahul Chemburkar

I will, as real as reverse engineering, I will start with the title which you use ‘Roti, Kapra, Makaan’. A coincidentally This is the title of a film from the 70s when in which a very interesting song is there, it says Polly Polly Taylor and Kaisa Jitney just made me lie to Jessa. So that actually, you know his answer of what we’re discussing today, water doesn’t have any colour, it is really actually neutral. And it is in a true way it is liberal. So, it is not you know, it is secular. Though it is not pseudo secular and also, when the water is like you know, I like to quote our Hill Hindi cinema has done a lot he will illustrate many examples. So as Nana particular season one movie called pura savani puja that’s a very interesting point on water. He sells he has come to sell water. Pani Joe head hugger cherub he said that to low ropes a robot coming back to order it in serious note, yes, today because it’s very difficult to imagine that we can have free drinking water. But I think it is a kind of a commercial or create commercially created liability means it’s very difficult, really difficult to you know, visualise this, but this difficulty if you see has sprung up only just only a little more than two decades ago. From the 90s you see that we started having bottled water, right? So that time I remember now no one remembers that because we have a short lived memory. So no one remembers that. Buying water also was something like Okay, why are we because in the first five years of the 90s, which I was in college, I remember when we used to go for study tools, we didn’t carry any bottled water, we had the same we drank the same water on the railway stations, which is still pure water, nothing more and nothing less, but the way you envelope or package it. So therefore bottled waters started becoming I’m not talking we’re not talking about spring water or distilled water whatever. But bottled water started being more reliable, because it was actually imbibed on the mindset. So that it is very, we need to shed our kind of you know, superstitions and we our kind of you know, that gimmicks that is one thing which is needed. I may sound a little absurd, but I think the reality. Another aspect is that how the pyaavs can play a role in this. Definitely as the government and the community as a whole needs to actually play a role. I see opportunity for the players playing a role of not only creating watersports, but creating pore spaces which are culturally vibrant. Therefore I call it cultural cause pieces right so you open someone cause in the whole city comes there to drink water buddy it is not only drinking water. It’s like taking a cultural pause so you connect with the plough and accordingly while connecting with the plough because it is creatively designed. It is very soothing to see and it is very soothing to us. Because it’s very psychological for us, just imagine when you bring water in the olden days the water actually used to use your hands. yeah these are all observations and these are my personal observations. Yeah slowly when you start using even a container, a lota actually has more kind of cultural Connect then a plastic glass, brass Carlota Tommy Carlota has more correct. So today, one of the first years which I was lucky enough to restore was called acacio ji right fountain, which is like a big canopy. It is like a chatri. At the chatri is like a very…

Vaissnavi Shukl

It’s a pavilion of sorts..

Rahul Chemburkar

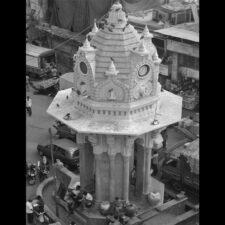

..a very pious and sacred place in Indian society. You have chatris, in dedication of someone, if you go indoor, you have the shin, the shin de chattery, and many more whatsoever. So it is fine of a church for three years like a canopy, as you mentioned, it’s an octagonal base, about that rises a shrine, it is adorned by different motifs like the elephant, the peacock, the Nandi or the Bullock. And around in between this the very act of drinking water is created through all the ports of water that are collected in other ports, and a person sits there and he takes the money in his sub jello. And that is the way you actually know, that is this I experienced this happens today I’m not directing your charity. If I go there, they the the community the people around that day very fondly call that place as a favera for what again, is the fountain they don’t call it is the Dell not call it a papini company Chi Ferrara, so piao favera all these are cultural connects, what I’m trying to say is that all this watersports already are at a very strategic locations in the city. So, therefore, as part of the whole revival, my firm must have done projects when we are appointed by the Mobil Corporation, you know, commissioned to restore the house, we what we did was we created a we, you know, conceptualised a heritage pal circuit, and those are almost like 30 pounds, and we are slowly slowly restoring them, what what we found was that already these are at strategic locations. So drinking water facility comes very likeable, you don’t have to justify the only thing what we have to do is that. Luckily, all these powers were part of water, you know, during the colonial times, when the water came into the city through the pipes, so, this had pipes or supply water pipe supply, but it was to gravitational that time the water was just flowing, today you have to supply water through a water tank. Luckily, Mumbai city has potable water. Today also many people bring direct water, but still to be safe, we are having industrial filters. So we may do another experiment with another restoration of the pyaav where we have installed the industrial filter, we pulled over a tank, underground tank and we facilitate data continuous water flow is started. The house today really could be instigators, and facilitators as mainly drinking water fountains at the same time creating cultural Connect, and socio cultural tourism also. So you know, it’s like multidisciplinary, you you provide drinking water facility, you create a portion it is in terms of sports, where the tourism can flourish. At the same time, the whole social hierarchy, the social connect through various, you know, people who used to provide water, people who used to, you know, there could be job opportunities like you, you would actually have some security around the house. So these are all things which can slowly it’s like ecosystem. You save the plough, you save the city.

Vaissnavi Shukl

I wanted to go back to your practice, because you mentioned you’ve been working with Balmain, Ansible, cooperation and with the government a fair bit. And in your practice of restoring the past, a significant aspect of the project is the creation of cultural spaces around these pyaavs. And to me this was really fascinating because when we look at typical restoration projects, we tend to isolate the object from its surroundings and focus on the upkeep only of that which is restored so we’re kind of not looking at it. neighbourhood or what lights around it or anything but that thing that is restored, it’s almost like a gem that’s polished but you’re not looking at anything else. And even in the case of the bows, one could just have restored the bows and left it at that hypothetically speaking, but you have a very different take on how a pyaavs could become a locus of cultural activities in a particular neighbourhood. Tell us more about this approach of kind of extending or at the the idea of yeah, extrapolating the idea of restoration not only to the object, but the context or the surrounding or the neighbourhood within which it lies.

Rahul Chemburkar

Okay, when the first pyaav which I restored, when when we actually landed on the site, I saw it in a very deliberate condition, like it was encroached upon, it was quite quite almost like two storey high canopy structure and almost a metre high plinth on which it was resting, then you can imagine in a city like Mumbai, this space has so much value, obviously, it was encroached upon sorry, okay, I will not use the word encroach. I meant that it was this the people around were owning it in their own way, I put it in a very positive way, because you know, in that dilepton condition also person used to sit there and used to be water, but the conditions were not in the way you would say very aesthetic or the way it used to be there was a tea stall or which we call a chai tapri on the steps, this fountain has a clock tower almost like 150 to 200 square feet, you know 150 square feet area, where a person can you know, slip. So, obviously person had created this accommodation there, that way it was encroached upon and very interesting tree was growing out of the hole, you can imagine the whole scale illustration in front of you, what we what I observed was that so, we started to work there, we current time, that whole curve, we started to work in that PC Street, slowly the people also actually you know, they they took it very positively we thought it they will actually start opposing to it looks very positive. And when we inaugurated when we actually completed the Restore, people all stuck and they said, okay, yada, yada. If this was what we were, you know, this was in mid summer, our whole locality, we were not aware of this, and that there was a Jean de rosette who actually funded it. So that was the first public private funding which happened to any fountain in the city. They actually had a big inauguration event. They called the CME, they called the chief minister to be inaugurated, there was a red carpet, there was ribbon surrounded, they cut the ribbon, they lined up to bring water, it was like a celebration. They started owning it in their own way, but in a positive way. And therefore, I was very pleasantly surprised when I came across a pamphlet of a grocery shop in that locality. And the grocery shops have their typical way of you know, printing the pamphlets, whatever Yeah, em into Hiya, piggy, who will die, I get rice, I get this, I get that. And they have some interesting kind of, you know, some as they are in their way they have their own aesthetic, they will put some, you know, some hero in or some TV star or some actors photo. What interested me was the the pamphlet in the central place, this guy was printed. And that was a very positive note that this society actually connects with it. What can heritage conservation or restoration do that actually gave me the answer that you know, or is what are we doing? We actually, when we talk about heritage restoration or heritage conservation, or heritage as a in totality, don’t we sometimes go into a utopian world of ourselves? We do we do we really do. We create a disconnect or instead of creating I’m not saying today there there I’m not saying it’s a pattern everywhere, but still I think more has to be done to connect to the society. Yes, of course. Many efforts have been done from all the sectors definitely I know that. But I found a very different to vo that allow the participation of the people hmm they they understand what exactly has been done and they take it take the story idea to just reveal mediator and I think that is what we are as a as a heritage enthusiast and architect. I think I I’m a custodian of what has been done by the previous generation. And I have to just take it ahead for the next generation. And therefore I think the society new don’t have, we don’t have to actually do what we have to just do a bit debt, okay, I have rescued the house. Now, you only create a kind of a module, or you create a kind of a system in which it goes ahead. But that system should allow people participation, the how that can happen. I make it a point I go to these sites, whenever someone comes there, they want to see something of Mumbai, I make it a point that I take them to the site, but not as a very celebrated heritage walk. I take them very casually. I bet Okay, you have a stroll, you go there and you land up there. The people there they greet me Saba, JoJo lilu, you know, that actually, you know, creates a correct,

Vaissnavi Shukl

I completely get that our role as designers, as architects is that of an enabler almost to go and reset and recharge this infrastructure that was always there. But I also constantly keep you know, wondering why it died in the first place, like the community within which these payoffs live, they were always there now everybody gets excited once you restore them. But if they’ve died in the past, how do we ensure that it doesn’t happen in the future? Because I mean, the times change sometimes the people change, but a lot of these places people have lived there for generations and they literally like seat every day. So why why do they need shy away from this question? Like why do you need somebody from the outside to come You know, this very Saviour complex a fluke was there in what you have and you know, you should rejoice this and it’s a wonderful thing, and then suddenly everybody’s proud of it, but why does it go back into the cycle of death and decay?

Rahul Chemburkar

So, definitely, we are not indicted one that we came in we actually enlightened the society. First thing I’ll as I told you, I will not shy away from this question. I experienced that after I restored the two examples, which I gave you are really case studies to be the case arena like fountain is still there, the people are you know, the trust is there they are pointed to security. So therefore, a little upkeep You know, it is it is being maintained. A very contrasting example is the of the another pyaav which was admitting a kabutar khana. As you know, the kabutar khana has its own cultural, kind of important advantages.

Vaissnavi Shukl

Explain what a kabutar khana is for everybody is not from India, cause it’s fascinating.

Rahul Chemburkar

Yeah, I know. So therefore, I’m saying, in Indian society, kabutar khana is a place a designated place, if I technically they would decide for bird feeding, and specifically bird feeding, I don’t have a kabutar khana, as we know, but the pigeons have their own kind of, you know, health hazard, which is very, very, very consciously taken up by many environmentalists in the city and all over the world, I think in mainly in India, that the kabutar khanas today should be history because they are becoming a kind of a liability in terms of health hazards. But to defy the governor of Canada is it’s a designated place for bird feeding mainly specially for the pitchers because it is considered pious, in many societies, many communities. So the day the grains are, you know, pulled there and all they’re sprayed over in that designated place. Another pyaav called Qatari PL, which is very staticy located right in the foot area opposite to the General Post Office, it is a mixture of a computer colour or bird feeding area and a pyaav or drinking water fountain. So, when again, there was a lot of encroachments etc, I learned that it is to be restored both the computer and up the house, but we took care also that we tried to the design itself was very beautifully done that you could segregate that through no small dividers, the birds would be we will not come very near to the fountain after it was inaugurated. What was what I had, I had been behind a corporation. Unfortunately, the maintenance agency backed away and then there was no proper maintenance was not done. And today, on Saturday, the lockdown also started and what happened because of that, slowly, the people who were taking care The computer cannot start. They increased again they shifted the dividers then one end of the cover the car was there. So, so, therefore, because the bird feeding activity started becoming more aggressive, you can even understand the bird droppings etcetera, etcetera started happening near the power game and the cleaning also not not done. So, the pyaav which was restored very elegantly, the water supplies still going on, but today, you can’t really go there and drink water because it is not because it is lacking the maintenance right. So, therefore, what we have done now is that when the restoration of any pyaav would happen, the technical way is that you come, we bring out we there are tenders which are floated by the Mumbai Corporation, we being the desire the conservation architects do the whole tendering. So, we put a clause that the contract registers itself with do the maintenance for three years. So, that the first step that the house will be maintained, because today you need to take that care as you rightly mentioned that there are two aspects one is negligence other is that people are not aware how to maintain it. Now, coming to the other part is that how this house actually landed up being through its estate, there are two reasons mainly, one is urbanisation, you see the towers getting the use of towers stopped after the free water flowing stopped, when the waters went into the households through pipes initially in the suburbs of Mumbai, if you see if you know the city of Mumbai, it’s the Metro Police today. So, there is a metropolitan region of Mumbai, where you have the Island City, the main city and then there are the Eastern and the western suburbs. So the the central and western suburbs to those suburbs were mainly rural areas or semi rural areas, they had water sports in town the you know whatever drinking water facilities in a natural way like the wells they had wells today also there are wells, though city of Mumbai also had a lot of ways three drinking water wells Okay, partly question and answer which is hidden in your question is that why we should ask that why the pyaavs are only limited to the island city of mobile, why they are not if you know the city or just to illustrate a city for our listeners, that Mumbai city actually has grown linearly from out to north. Colaba was the southern tip is the southern tip. And then from there towards the north. So the city has grown east to where the city has not grown much the suburbs have grown afterwards. So from south to north, on the north side, there is a place called siren, which is called it’s the border of the island city of movie, you find a palace only in this island city, because that is the that was a city which was main into the governance of the British. Afterwards, even though it grew the this the villages in the suburbs, we had their own water points in form of the wells I didn’t need any powers. What happened was that till the 70s movie city also if you see the through the water infrastructure, all the households started getting water that was one element that public drinking also mainly to that extent must have reduced. So slowly and slowly the water supply also started getting receded. So, to be you have only two to three hours continuous water. So therefore, they do they became remnants of the past slowly when it is not in use, they get started used you know getting little abused also or maybe the period of maybe the post independence period if you see slowly that is lot of urbanisation happening the main focusing mainly on urbanisation the revival is toward the more conservation is toward the heritage kind of you know revival. You see coming up slowly from the 80s. So, when the till that time, not only the house many street furnitures like the house the milestones, lamppost benches, manhole covers, which were of the yesteryears and which had lot of aesthetics, because slowly if you see in the olden time, there is aesthetics at a very micro level. Yeah, you find a very simple kind of commemorative stone, which is very elegantly called today it’s very done very technically, huh. So therefore, till the 70s or the 80s 1980 You see all this going into distress. And then right Mumbai being the first city de style decided to draft a kind of heritage resolution and we had a heritage list coming out in the 90s there was a lot of documentation which is happening. And as part of the word documentation, many of the drinking water fountains also found place in the list, but still, it had to be something like the first decade of the 21st century that slowly we started understanding that Okay, these are something which could be revived, as, you know, as facilities. So, that’s the whole history that how they get caught into distress and how slowly they are getting revived.

Vaissnavi Shukl

Very, very, very fascinating. I did not know that as backers. Mostly, you know, somebody who does not know the backstory would always think that these things because of changes in technology, because of changes in infrastructure would or just ignorance would would go into decay. So, you are associated with the Mumbai water narratives and Confluence, which is supported by the living waters Museum, and their galleries highlight the various intersections of water with the built heritage, with people’s livelihoods, culture, equity and public health. Can you elaborate a little on the work being done by you and your colleagues at this Confluence, and we’d also love to know what is next for you.

Rahul Chemburkar

So living water museum is a very interesting, very intriguing kind of initiative, Sarah, who is the founder who is the main backbone to this last year, many like me, many of us were contacted in the city or in our capacities, who have whoever working in different capacities towards water. And it was it was like tangibles and intangibles of water heritage, to be very specific. So my water narratives mainly was the term coined as for specific for the virgin for mobile of Ling water museum. We contributed in creating this virtual walk for the first year online initiative event, Cordingley conference, that is what you’re mentioning just now. So we actually created a virtual walkthrough of the of one stretch in the city which had different water fountains on the house. And we created as kind of a short to video short documentary, talking of the house, because that was one aspect of water where there are a lot of intent, tangible, but it had a lot of intangibles in it. So if you see the house It is it is if it doesn’t have a lot of intangibles, in terms of the socio cultural aspects, it doesn’t make sense actually. And the intangibles as I likely mean as I mentioned to you in the outset is that mainly the charity and association value, what is next the way it comes? I will try to see trying to connect with counterparts in India because I have my own profession I we are into heritage restoration was Sudan projects, but the houses become a passion of me and my team also. Interestingly, when I travelled to many places in India, after I came to no conscious way became conscious of the house. I found a similarity similar kind of, you know, initiatives or examples. In many cities like in play, you don’t have a PR but you have a house how there’s a kind of a you know, what you call it a system or maybe a kind of a water container, a stone water container, which is created at different locations in the city and moomba Cooney city had a during the pace was there was an aquatic duck, which was created and water was brought from one Lake outside today to the city and still in the water was flowing to till now displaying. So then, when I went to Jammu three years ago, I found some like, you know, cast iron pillars along the street, and it had those jaguar contemporary jaguar taps connected to it. So I asked them, “What is this these are”, these are melkus they look like decorative fire hydrants, but those were drinking water facilities. So what I found was that there are examples, maybe more Mumbai city stands separate because it has this interesting looking drinking water fountains. But I think this initiative can be taken collaborate many places so I’m trying to connect with the counterparts maybe now friends like you could also be the facilitators or maybe abroad also in in Euro in UK, where we have this drinking water fountains and try to just check that can we start a initiate, initiate some kind of you know interaction just interesting just to know it said okay there there are piles in Mumbai there are drinking fountains in Italy and how can that could be very insightful? I don’t know the way ahead maybe that’s just one step. Interestingly the there is Sir kawachi jogging who has donated most of the cows in Mumbai. He has donated one cow in in Bombay quarter profit market today it is called the magma flea market. So, there are two piles and there is one interesting fountain there is this fountain which is very beautifully cow It looks like a catheter and it’s a replica or a twin brother is dairy London which is donated by Sir Kawasaki. So so so that was that is what I’ve tried to see. Now coming over to this other house in Crawford market just for your information if you land up in Moby and now I will take you on a ride. There are there is another pyaav which which has a crown on it. There was some donation collected by the shop owners and when when the king actually visited first time in Mumbai that is actually created a club and as an interesting bow arrow fountain I don’t know it’s a ledger founded on a mix of a cow, which is sculpted It is called immerse and founder which showcases the flora and fauna of Southeast Asia in those times. And the interesting part is that it is sculpted by Lockwood Kipling, who is the father of Rudyard Kipling. He was the Dean of this Sir J.J. College of Art.

Vaissnavi Shukl

Wow, that’s an a very interesting piece of trivia but I can’t wait to see what’s to come next. And I will definitely bring you the next time in Bombay. Now we have it on evidence on the podcast that you’re going to take me around so very excited for that as well. Hopefully, travel becomes easier and that we get to meet in person. So thank you so much for being here today. Rahul. I’m very glad I came across your work and I’m so glad you’re here to share it with everyone.

Rahul Chemburkar

It’s my pleasure that I was able to share such insights which have excited me and so these are considered waters which we should allow to flow and that should actually connect the rivers should connect someday at some place.

Vaissnavi Shukl

Special thanks to Ayushi Thakur for the research and design support, and Kahaan Shah for the background score. For guests and topic suggestions, you can get in touch with us through instagram or our website through our website archoffcentre.com, both of which are ‘archoffcentre’. And thank you for listening.